In 1972 Americans were engaged in a national debate over whether to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution. That debate informed discussion during Montana’s 1972 constitutional convention, and convention delegates enshrined equal protection in the “individual dignity” clause of its Declaration of Rights. Backed by this promise of equality, women’s rights advocates and members of the newly formed Montana Women’s Political Caucus, an organization of female state legislators, worked to reform Montana’s laws to erase sex discrimination. Through their efforts, the 1970s saw important steps toward equalization of Montana’s laws; however, the Montana Supreme Court’s conservative application of the individual dignity clause to sex discrimination undercut the potential for radical strides toward legal equality.

The “Declaration of Rights” in Montana’s 1889 Constitution had stated that “all persons are born equally free,” but the new constitution went far beyond that vague provision in its individual dignity clause. Working on the language for the state’s new constitution, delegate Virginia Blend of Great Falls proposed that the actual language of the Equal Rights Amendment be included in the Declaration of Rights. Instead the 1972 Constitution addressed the issue of gender equity in the constitution’s “individual dignity” clause, which guaranteed equal protection of the laws. Notable for its expansiveness, Article II, Section 4, of the 1972 constitution promised that “Neither the state nor any person, firm, corporation, or institution shall discriminate against any person in the exercise of his civil or political rights on account of race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas.” The clause links equality to human dignity and includes a long list of protected classes, making it, according to scholars Larry Elison and Fritz Snyder, the “most inclusive scheme of ‘equal rights’ of any known constitution.”

Though many of the delegates to the state constitutional convention assumed that the ERA would soon pass nationally, they specifically decided to include “sex” in the list of protected classes because they “saw no reason for the state to wait for the adoption of the federal equal rights amendment.” In light of the national failure to ratify the ERA, Montana’s statement of its commitment to gender equality became even more important.

Once the constitution was ratified, Montana lawmakers—particularly women lawmakers—began a push to align state laws and institutions with the constitution’s new guarantee of equality. The 43rd Montana Legislature (1973-1974) created three new state agencies to monitor discrimination: the Human Rights Bureau, the Equal Employment Opportunity Bureau, and the Women’s Bureau. The Human Rights Bureau, the administrative arm of the newly created Montana Human Rights Commission, was given the power to handle discrimination complaints. The EEO and Women’s Bureau helped place women and minorities in state jobs and spread information about opportunities for women, but both agencies lacked enforcement powers.

In the 44th Montana Legislature (1975), members of the Montana Women’s Political Caucus undertook a concerted effort to eliminate legal sex discrimination in Montana. Caucus members proposed bills, including ones that prohibited discrimination in government employment, reformed divorce and custody laws, and equalized the obligations of support between spouses. Not all of their proposals passed. For example, a bill making it illegal to patronize a prostitute died on the floor. However, other efforts to remove sex discrimination from property and criminal laws moved through and quickly were signed into law.

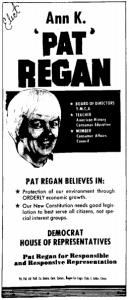

Two key factors facilitated the push for the legislating legal equality. Reapportionment shifted political power to Montana’s urban areas, which led to the election of more progressive Democrats. Accompanying that change, a surge of female legislators helped shift the agenda to shed light on sex discrimination. In 1971 only one woman, Dorothy Bradley, served in the state legislature. In 1975 there were ten women in the House and four in the Senate, including Geraldine Travis, Montana’s first and only African American state legislator. These numbers meant that women composed 9.3 percent of the legislature.

As legislators worked to rewrite Montana’s laws one at a time, the Montana Supreme Court could have facilitated the process by using the individual dignity clause to chip away at sex discrimination. In other areas of constitutional law, notably the right to privacy, which is also guaranteed by the 1972 constitution, the Court used the new constitution to forward a much broader set of protections than exist federally. By contrast, in the area of sex discrimination, the Court tended to overlook the Montana constitution’s equal rights provisions, relying instead on federal equal protection decisions to justify its determinations.

In spite of women’s gains in the legislative arena, the process of eliminating sex discrimination from the law through legislative action was slow, piecemeal, and ongoing, and the Supreme Court’s reluctance to facilitate the process undercut the radical potential of the individual dignity clause. As attorney Jeanne M. Koester has noted, “The Montana equal rights provision calls for an unequivocal ‘eradication of public and private discrimination based on . . . sex.’ Sex discrimination can be eradicated only if the Montana courts fully recognize this new right.” AH

For more on women’s participation in Montana politics, read Montana’s Postwar Women Politicians or After Suffrage: Women Politicians at the Montana Capitol.

Sources

Constitution of the State of Montana. Available online.

“Democrats Control State Legislature,” Kalispell Daily Inter Lake, November 7, 1974, p. 8.

Elison, Larry M., and Fritz Snyder. The Montana State Constitution: A Reference Guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2001.

Fritz, Harry. “The 1972 Montana Constitution in Contemporary Context.” Montana Law Review 51, no. 2 (Summer 1990), 270-74.

Griffing, Betsy. “The Rise and Fall of the New Judicial Federalism under the Montana Constitution.” Montana Law Review 71, no. 2 (Summer 2010), 383-93.

Hutchinson, Arthur. “Skimpy Funds Don’t Help Human Rights Panel.” Helena Independent Record, November 19, 1974.

Koester, Jeanne M. “Equal Rights.” Montana Law Review 39, no. 2 (Summer 1978), 238-48.

Malone, Michael P., and Dianne G. Doughterty. “Montana’s Political Culture: A Century of Evolution.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 31, no. 1 (Winter 1981), 44-58.

Montana Women’s Political Caucus records, 1974-1982, SC 2036, Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.

Nelson, Inga Katrin. “‘Each Generation of a Free Society’: The Relationship between Montana’s Constitutional Convention, Individual Rights Protections, and State Constitutionalism.” Master’s thesis, Portland State University, 2011.

“New Dawn in State Politics,” Kalispell Daily Inter Lake, November 7, 1974.

Robbin, Tia Rikel. “Untouched Protection from Discrimination: Private Action in Montana’s Individual Dignity Clause.” Montana Law Review 51, no. 2 (Summer 1990), 553-70.

Treadwell, Lujuana Wolfe, and Nancy Wallace Page. “Equal Rights Provisions: The Experience under State Constitutions.” California Law Review, 65, no. 5 (September 1977), 1086-1112.

“Virginia Blend Testimony Regarding Providing Equal Rights.” Montana Constitutional Convention Records, 1971-1972, Montana Historical Society Research Center.

Women’s Political Caucus Vertical File, Montana Historical Society, Helena.