In the fall of 1913, Jennie Bell Maynard, a teacher in Plains, married banker Bradley Ernsberger. The couple kept their wedding a secret until Bradley found a job in Lewistown and they moved: “No inkling of the marriage leaked out. . . . Mrs. Ernsberger continued to use her maiden name and teach school.” A year later, Butte teacher Adelaide Rowe eloped to Fort Benton with her sweetheart, Theodore Pilger. They hid their marriage for three years. Maynard and Rowe were just two of the many Montana women teachers who married secretly—or didn’t marry at all—in order to keep teaching.

The story of “marriage bars,’ or bans, does not unfold linearly. Livingston lifted its “rule against the employment of married lady teachers” in 1896. The Anaconda school district also allowed married women to teach in the 1890s, but in 1899, facing lower than anticipated enrollment, the superintendent sought the resignation of the district’s one married teacher, explaining that Mrs. Foley “is married and is not in need of the salary which she draws from the schools.”

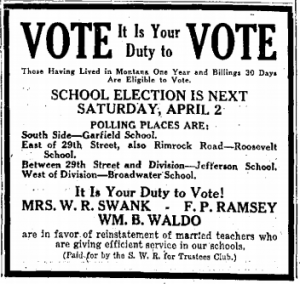

The idea that married women did not need the income, and that “hiring married women would deprive single girls of opportunities,” was the most common rationale for marriage bars. On the other hand, advocates for married teachers tried unsuccessfully to reframe the debate in terms of student welfare. Mrs. W. J. Christie of Butte argued in 1913 that “The test of employment should be efficiency and nothing else.” Mrs. James Floyd Denison agreed: “When a married woman has the desire to go from her home and to enter the school room . . . it must be because her heart and soul are in the teaching work. Under those circumstances, if she is allowed to teach, the community will be getting her very best service.” Unconvinced, Miss Ella Crowley, Silver Bow County superintendent of schools, believed that a married woman’s place was at home. While she recognized the value of experience, she also believed that if women taught after marriage, “there never would be any room for new teachers or for girls.” Continue reading “Must a woman . . . give it all up when she marries?”: The Debate over Employing Married Women as Teachers