Amid the ruins of the Fort Shaw Industrial Indian Boarding School, a metal arch and granite monument honor ten Native American girls who overcame separation from their families and forced estrangement from their Native cultures to become the finest female basketball players in the country. Declared the “World Basket Ball Champions” in 1904, the girls from Fort Shaw also deserve praise for having triumphed over extraordinary life challenges.

In 1892 the federal government opened the Fort Shaw Indian Boarding School. Such off-reservation schools were designed to break the chain of cultural continuity by removing children from their tribal communities. The schools’ paramount educational objectives were cultural assimilation and English language fluency. Students were trained for employment in domestic services, industrial labor, and farming. Classes in music, theater, and physical education rounded out their instruction.

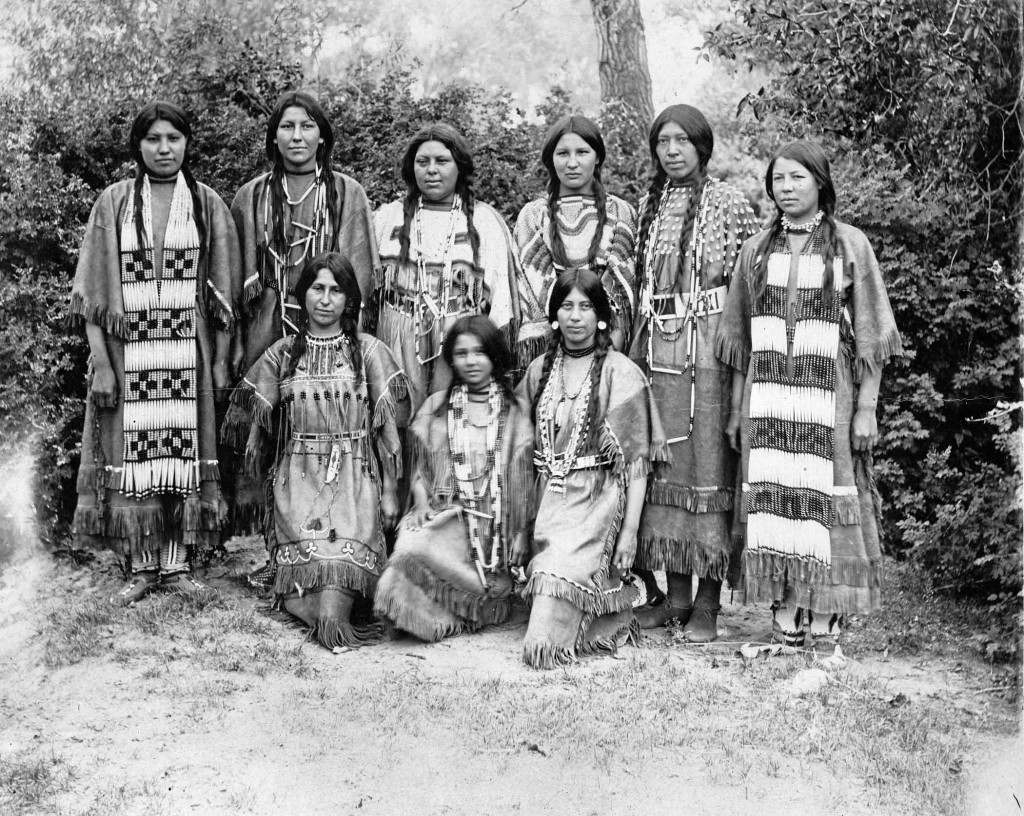

The girls who formed Fort Shaw’s famous team had much in common. Although they came from several different tribes, nearly all of them were daughters of indigenous women and white men. Many of the girls were multilingual, several spoke English conversantly, and several had siblings at Fort Shaw.

Many of the girls had also known tragedy in their lives. Four of the girls had lost their mothers, and two had lost their fathers. While attending Fort Shaw, two were orphaned and yet another girl lost her father. Two had sisters who died from infectious diseases at school, and several had brothers or male cousins who ran away from Fort Shaw, one of whom froze to death in the attempt.

Boarding school demanded that the girls relinquish their indigenous cultural identities, at least outwardly, and adopt white cultural behaviors. While discovering friendship and support from one another, each of these girls also drew on her own inner strength, courage, and intelligence to surpass expectations and to excel as a student and as an athlete.

When Josephine Langley, their physical culture instructor, introduced basketball at Fort Shaw in 1896, the sport was in its infancy. The strenuous game instantly delighted the female students, whose physical activities were generally more restricted at school than they had been at home. When the Fort Shaw girls gave their initial intramural basketball demonstration in 1897 at the year-end closing ceremonies, the three hundred spectators responded with enthusiasm to the first high school basketball program in Montana.

However, lack of funding and lack of opposing teams kept the Fort Shaw girls from playing competitive basketball until the fall of 1902, when intramural coach Josie Langley (Blackfeet) joined Emma Sansaver (Chippewa-Cree), Belle Johnson (Blackfeet), Nettie Wirth (Assiniboine), and Minnie Burton (Lemhi Shoshone) to form that first team. Fort Shaw won its first competitive game, against Butte, but lost against Helena High a few days later. Despite the loss, the Montana Daily Record ran a front-page article complimenting the Indian team’s talent. In January 1903, Butte Parochial High School handed Fort Shaw its second—and last—defeat.

Montanans’ enthusiastic support for the Fort Shaw team grew with each competition. Unable to host a game at their own school, the Fort Shaw team played “home” games at Luther Hall in Great Falls, the only place big enough to accommodate several hundred fans. By the end of 1903, the team, now expanded in numbers as well as fame, had even defeated Missoula and Bozeman’s college teams, as well as the reigning state champions, Helena High.

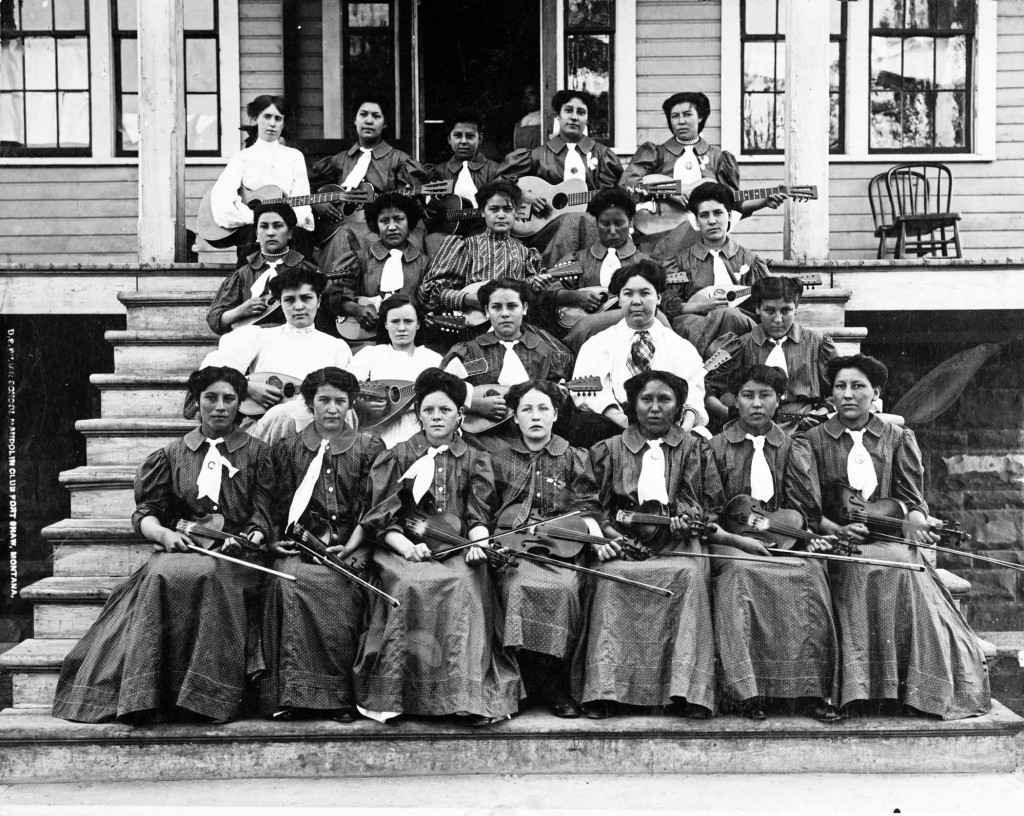

Fort Shaw Superintendent Fred Campbell quickly grasped the benefits of a competitive basketball team. The girls were mastering teamwork, building physical agility, and gaining self-confidence. Anti-Indian prejudices seemed to be fading as white Montanans’ exposure to team members and their accomplishments increased. Fort Shaw’s band and its mandolin orchestra entertained spectators before games, and newspapers gushed about the girls’ talent in ballroom dancing at after-game assemblies. The team’s fame soon opened up even greater opportunities to showcase the school’s successful, and transformative, education of indigenous children.

In 1903, Campbell received an invitation to send students to participate in the Model Indian School at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. The model school contrasted with exhibitions of indigenous peoples’ traditional lifeways and intended to validate America’s policy of forced assimilation. Campbell didn’t hesitate to choose the ten girls on the current basketball team as his delegates. Four of the members of the 1902 team—Belle Johnson, Emma Sansaver, Minnie Burton, and Nettie Wirth—joined the girls who had since rounded out the team: Gen Healy (Gros Ventre), Katie Snell (Assiniboine), Gennie Butch (Assiniboine), Rose LaRose (Shoshone-Bannock), Flora Lucero (Chippewa), and Sarah Mitchell (Assiniboine). Nettie’s older sister, Lizzie Wirth, accompanied them as chaperone and substitute player. As exemplary students, star athletes, and models of assimilation, the team would demonstrate Fort Shaw’s success to the world.

The girls played fund-raising games en route to St. Louis, often encountering anti-Indian attitudes among the spectators. At the fair, they divided up for 5-on-5 exhibition games before captivated audiences, while across the street male athletes competed for medals at the Third Olympiad. Late in the summer, when they received an invitation to stage an exhibition game at the Olympics, the girls played before thousands of cheering spectators. By the close of the fair, the girls from Fort Shaw Indian Boarding School in Montana were being celebrated as the basketball champions of the world. They sealed that title with back-to-back victories against a Missouri all-star team, the only team to brave a competition.

With all they had to overcome, and all they had to leave behind, the girls’ glory was well-earned. Their achievements demonstrated their ability to excel despite personal tragedies, destructive federal Indian policies, and limitations imposed on them as Indian women in turn-of-the-century America. Even today their victories in life and in basketball continue to inspire us and make us cheer. LKF

Want to learn more? Read Linda Peavy and Ursula Smith’s article, “World Champions: The 1904 Girls’ Basketball Team from Fort Shaw Indian Boarding School,” in Montana The Magazine of Western History 51, no. 4 (Winter 2001), 2-25. You can find links to the full text of all Montana The Magazine of Western History articles relating to women’s history here.

Sources

McNeel, Jack. “Before Schimmel: The Indian Women Who Became Basketball Champions.” Indian Country Today Media Network. October 27, 2013. http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/10/27/story-how-indian-women-became-basketball-champions-still-told-151912 Accessed January 27, 2014.

Peavy, Linda, and Ursula Smith. Full-Court Quest: The Girls from Fort Shaw Indian School, Basketball Champions of the World. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

___. “Unlikely Champion: Emma Rose Sansaver, 1884-1925.” In Garcear-Hagen, Dee, ed. Portraits of Women in the American West. New York: Routledge University Press, 2005, 179-208.

___. “World Champions: The 1904 Girls’ Basketball Team from Fort Shaw Indian Boarding School.” Montana The Magazine of Western History 51, no. 4 (Winter 2001), 2-25.

Playing for the World. DVD. Montana PBS. 2009.

How great what they did …

How sad what we did TO them –

I don’t think you understand, Ms Brantley. The girls of Fort Hall are prime facie evidence that Indian people stand great amongst ourselves, and the girls of Fort Hall were just provide more evidence that victory is a state of mind, and not acceptance of pity.

Fort Shaw not Fort Hall. Nettie was my mother’s aunt…Lizzie was her mother

Belle Johnson is my great grandma any info you can give me, please

Barbara J Tabler

Belle Johnson was also my Great grandmother, my grandfather was her son, his name is James, Jimmy Hix, Arnoux

I am related to Sarah Mitchell, there are several descendants living at Fort Peck Indian Reservation MT and scattered around the country. We have Mitchell family reunions every couple of years either at the Reservation or at various Pow Wows around the country. The next one is at the Stewart Fathers Day Powwow on June 14-16, 2019. Carson City NV.

Wow– WHAT A GREAT STORY

I’m glad that it worked out to post this with the biographical notes about each girl popping up when the mouse hovers over each one’s name (underlined). Thanks for making that possible!

Minnie burton was my great grandmother I just happen to be checking t v station chanels when I saw the p b s story about her, I never knew about her until then, I sure am glad I was watching T V that, makes me proud to be a native american ( full blood ) thank so much.

I am somehow related to Emma Sansaver. All I know is My Paternal Flo Hamilton grandmother was married To Jack Sansaver. I am so proud.

When I was in grade school, we lost to a girls’ team 49-33!

http://www.gballmag.com/cc-poise.html

When I was in 8th grade, our champion team lost to a team of our age group to an All-Girls’ Academy!

Here is the story http://www.gballmag.com/cc-poise.html

Doing a project on this very helpful

Emma Sansaver was my cousin and very proud of her

I am a great granddaughter of Belle Johnson.I have read so much about this amazing women.I am having NO luck in locating her burial location or by chance existing family. Please contact

Belle Johnson my great grandmother.Just recently made aware, any information would just be wonderful, also information on burial site?I will fly and rent a car to visit her final resting place

Gen Healy is my grandmother.