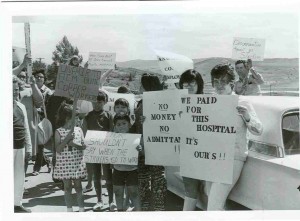

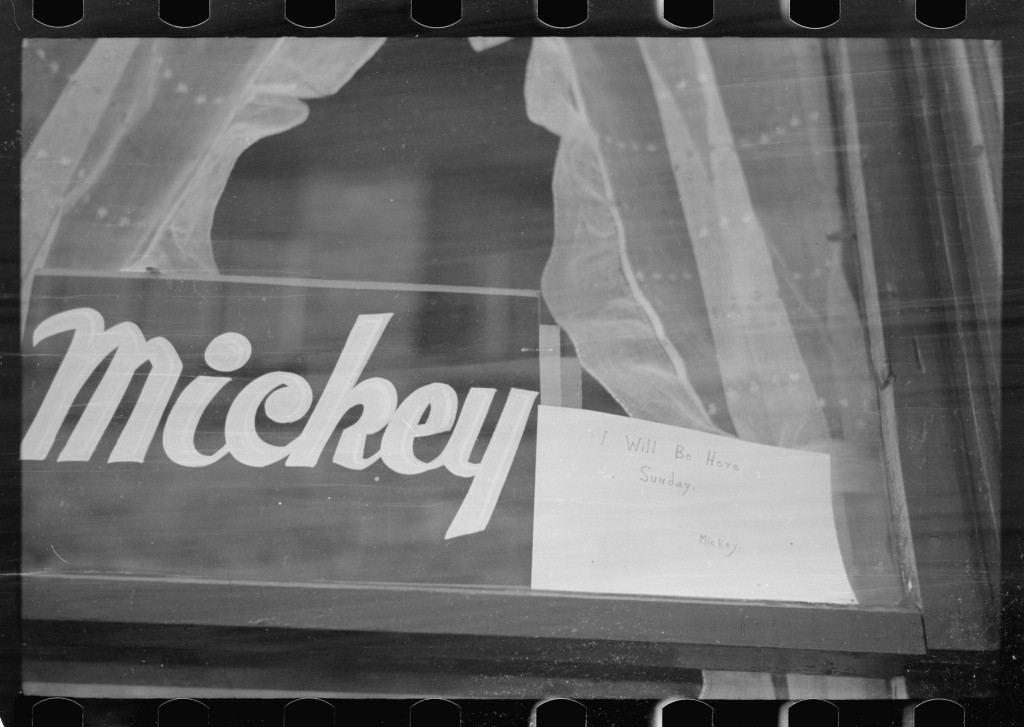

“The girls range in age from jail bait to battle ax,” wrote Monroe Fry of Butte prostitutes in 1953. “[They] sit and tap on the windows. They are ready for business around the clock.” Fry named Butte one of the three “most wide-open towns” in the United States. The other two—Galveston, Texas, and Phenix City, Alabama—existed solely to serve nearby military bases, but Butte’s district depended upon hometown customers. Butte earned the designation “wide-open”—a place where vice went unchecked—largely because of its flamboyant, very public red-light district and the women who worked there.

For more than a century, these pioneers of a different ilk, highly transient and frustratingly anonymous, molded their business practices to survive changes and reforms. As elsewhere, the fines they paid fattened city coffers, and businesses depended upon their patronage. Reasons for Butte’s far-famed reputation went deeper, however, as these women filled an additional role. Miners who spent money, time, and energy on public women were less likely to organize against the powerful Anaconda Copper Mining Company. As long as the mines operated, public women served the company by deflecting men’s interest.

The architectural layers of Butte’s last remaining parlor house, the Dumas Hotel, visually illustrate a changing economy and shift in clientele from Copper Kings to miners. Today, the second floor retains the original suites where Butte’s elite spent lavish sums in the high-rolling 1890s. But the ground floor’s elegant spaces, where staged soirees preceded upstairs “business,” were later converted to cribs, one-room offices where women served their clients. Continue reading Red-Light Women of Wide-Open Butte