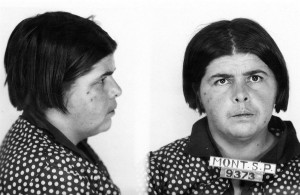

A former member of the Communist Party who could brag of an FBI file over four hundred pages in length that monitored her political activity, Elsie Gilland Fox was a tireless and formidable activist and community builder from Miles City, Montana. Her modest upbringing in rural eastern Montana shaped her sense of economic justice, and Fox spent her life advocating democratic social change to alleviate the inequalities of the capitalist system.

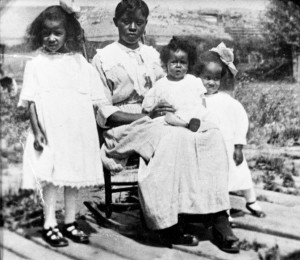

Elsie Gilland was born on a Powder River ranch south of Broadus in 1907. Her parents divorced when she was four, leaving her mother, Marcie, to homestead and raise three young children by herself. Living on the edge of poverty meant that each member of the family had to contribute to the economic production of the homestead, and Elsie recalled planting potatoes and cleaning the chicken coop to help out. From her brother, she also learned how to hunt and fish, and fishing would become her lifelong love: “Whenever I’ve had a real crisis, fishing has brought me out of it,” she said in later years. “It’s being out of doors, the movement of the water, hearing the birds sing. Lots cheaper than a psychiatrist.” Continue reading “May the World Be a Peaceful and Happy Place to Live”: The Lifelong Activism of Elsie Gilland Fox