In 1876, the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho people defended their sovereignty, their land, and their lives against the United States. The Rosebud and Little Bighorn battles proved the tribes’ military strength but ultimately contributed to tragic consequences for the victors. A young Cheyenne mother, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, fought alongside her brother and husband at both battles in defense of Cheyenne freedom.

Buffalo Calf Road Woman lived during the Indian wars, an era of extreme violence against the Native inhabitants of the West. American settlers frequently trespassed onto tribal lands, and tribes retaliated by raiding settler camps. Several brutal massacres of peaceful tribal groups by whites led to widespread fear among the tribes and shocked the American public. Such violence increased tensions in the region.

After Lakota chief Red Cloud decisively defeated the U.S. military in 1864 to close the Bozeman Trail, the United States negotiated a peace treaty with the Lakotas. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty established the Great Sioux Nation, a huge reservation encompassing present-day western South Dakota, and designated the unceded lands between the Black Hills and the Bighorn Mountains, including the Powder River country, for the Indians’ “absolute and undisturbed use.” Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho bands also occupied this region.

In 1874 the United States government sent Gen. George Custer, who had led a massacre against the Southern Cheyennes four years earlier, to explore the Black Hills. When the expedition found gold, the government sought to buy the Black Hills, but the Lakotas refused. Fearing conflict, the government ordered all Indians who remained on this unceded tract to go to the Sioux reservation by January 1876, declaring that troops would deal forcibly with any who refused. However, the region was critical to their existence, since it remained prime hunting ground for what was left of the once vast buffalo herds.

The tribes were caught in a double bind: retreat to the reservation and possibly starve or continue to occupy their full territory and risk attack. In the summer of 1876, several hundred Cheyennes and Lakotas camped in the Powder River and Little Bighorn valleys. Buffalo Calf Road Woman, her husband Black Coyote, their daughter, and Buffalo Calf Road Woman’s brother, Comes In Sight, were among the Cheyennes in these unceded lands west of the reservation when Brig. Gen. George Crook’s troops arrived in the area.

Earlier that year, Crook’s men had burned a Cheyenne village. Not wanting to face the same fate, Cheyenne and Lakota warriors attacked Crook’s troops at the Rosebud on June 17. When soldiers shot Comes In Sight’s horse and he fell, Buffalo Calf Road Woman rode into the heart of the battle. Amid a shower of arrows and bullets, she helped her brother cling to her horse and carried him to safety. At the end of the day, Crook’s command withdrew, unable to defeat the tribes. The Lakotas and Cheyennes fled, some joining those camped on the Little Bighorn.

Eight days later, Custer’s regiment attacked the Cheyenne and Lakota families at the Little Bighorn. Most of the women took their children and retreated to safety, but some rode onto the battlefield, singing “strong heart” songs of encouragement as they watched for fallen or injured men. One of these women was Antelope (Kate Bighead), who later recalled seeing the lone woman warrior:

Calf Trail Woman had a six-shooter, with bullets and powder, and she fired many shots at the soldiers. She was the only woman there who had a gun. She stayed on her pony all the time, but she kept not far from her husband, Black Coyote. . . . At one time she was about to give her pony to a young Cheyenne who had lost his own, but I called out to them, “Our women have plenty of good horses for you down at the river.” . . . She took the young Cheyenne up behind her on her own pony and they rode away toward the river. This same woman was also with the warriors when they went from the Reno creek camp to fight the soldiers far up Rosebud creek about a week before. . . . She was the only woman I know of who went with the warriors to that fight.

Following the tribes’ victory at Little Bighorn, the United States redoubled its efforts to hunt down off-reservation Indians. Over twelve hundred Cheyennes took to the hills, pursued by U.S. troops. For many months, several Cheyenne bands eluded capture, fleeing their camps as the soldiers attacked. It was during this period and under these conditions that Buffalo Calf Road Woman had a second child.

By the summer of 1877, the Cheyennes, facing starvation, surrendered. Instead of returning them to the Sioux reservation, however, troops forced-marched them fifteen hundred miles to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and imprisoned them at Fort Reno. Nearly fifty Cheyennes died en route, and many more succumbed to malaria and exhaustion in the extreme Oklahoma heat. In September 1878, some three hundred Cheyennes led by chiefs Dull Knife and Little Wolf escaped and headed north toward home.

The leaders separated near Fort Robinson, Nebraska, and Buffalo Calf Road Woman’s family continued north with Little Wolf. In a rash act, Black Coyote killed a soldier. He and his family were captured and taken to Fort Keogh in Montana, where nearly three hundred Cheyennes were already imprisoned. There, Buffalo Calf Road Woman died from diphtheria in the winter of 1879. In his grief, Black Coyote committed suicide.

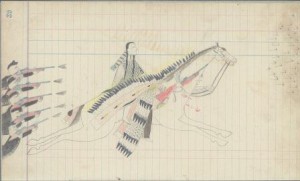

Cheyenne warriors recorded Buffalo Calf Road Woman’s courageous ride into the Rosebud battle in a ledger drawing. Today the Cheyenne people still call the battle site “Where the Girl Saved Her Brother.” Each January since 1999, Cheyenne runners participate in a four-hundred-mile memorial run from Fort Robinson, Nebraska, to the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in honor of their ancestors who fought for their freedom and sovereignty, including Buffalo Calf Road Woman. – LKF

Sources

Healy, Donna. “American Indian Images: Northern Cheyenne History Told in Photos, Interviews.” Billings (Mont.) Gazette. August 6, 2006. http://billingsgazette.com/news/features/magazine/american-indian-images/article_7879faa3-6215-52d0-a2f4-731c6c04a064.html. Accessed October 17, 2013.

Hoxie, Frederick E., ed. Encyclopedia of North American Indians. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1996.

Marquis, Thomas. Custer on the Little Big Horn. Lodi, Calif.: End-Kian Publishing Company, 1967.

Michno, Gregory F. Lakota Noon: The Indian Narrative of Custer’s Defeat. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press, 1997.

Weist, Tom. A History of the Cheyenne People, rev. ed. Billings: Montana Council for Indian Education, 1984.

Little Bear, Richard, ed. We, The Northern Cheyenne People: Our Land, Our History, Our Culture. Lame Deer, Mont.: Chief Dull Knife College, 2008.