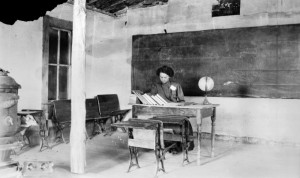

When Blanche McManus arrived to teach at a one-room schoolhouse on the south fork of the Yaak River in 1928, the school contained a table, boards painted black for a chalkboard, and a log for her to sit on. She had four students: a seventh-grade boy who quit when he turned sixteen later that year; a thirteen-year-old girl who completed the entire seventh- and eighth-grade curriculum in just four months; a sweet-natured first grader; and a lazy fifth-grade boy whose mother expected McManus to give him good grades. “I used to teach arithmetic and then go out behind the school house and cry,” McManus remembered. Like other teachers across Montana’s rural landscape in the early twentieth century, McManus relied on her own resourcefulness and creativity to succeed while facing innumerable challenges.

In the early 1900s, an aspiring teacher could obtain a two-year rural teaching certificate, provided she was a high school graduate, was unmarried, and passed competency exams in various subjects. Some high schools provided limited teacher training during the junior and senior years. Rural district trustees, some of whom had little formal education themselves, assumed students would become miners, wives, or farmers like their parents and therefore needed only a rudimentary education. They frequently hired two-year certified teachers fresh out of high school.

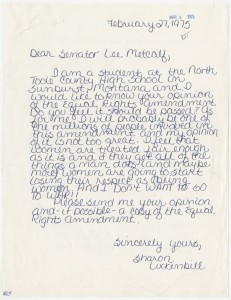

Nonetheless, when eighteen-year-old Loretta Jarussi applied for her first teaching position at Plainview School in Carbon County in 1917, the school board initially balked at her lack of experience. Then one board member declared they ought to hire Jarussi because she had red hair and “the best teacher I ever had was a redhead.” Jarussi got the job. Once employed, Jarussi felt she was “getting rich fast.” A female teacher in a rural school could earn sixty to eighty dollars per month at that time; a male teacher earned roughly 20 percent more. Continue reading “Be Creative and Be Resourceful”: Rural Teachers in the Early Twentieth Century